Poorer households to lose around £500 per year by end of decade, thinktank says – and why Reeves is saying the opposite

In her Today programme interview Rachel Reeves was asked about the Resolution Foundation’s spring statement analysis published this morning. (See 8.33am.)

This is what it says in its summary about how the government’s measures will cost poorer families around £500.

This is still early days for this government, but it could fairly be judged not just by this spring statement alone, but in the round – considering all the choices it has taken so far affecting family finances, including at the 2024 autumn budget. Taking everything together, the burden of adjustment looks less slanted – but poorer, disabled households are still set to take the biggest hit. More generally, a combined squeeze that reduces incomes by around 1.5% in the lower-middle reaches of the spectrum declines to only 0.5% at the very top.

Factoring those distributional decisions into the general outlook for growth and income makes for particularly grim reading. Across the poorer half of the country, the five years up to 2029 will see after-housing-costs incomes drop by around £500. In data going back to the early 1960s, larger drops for low-to-middle income families have only been seen twice before – in the sharp recession of the early 1990s, and then again in the immediate wake of the credit crunch. Disproportionate income reductions for sick and disabled people in poorer households are not going to help with any of these trends.

The Resolution Foundation uses its own disposable household income figures that are different from the real household disposable incomes (RHDI) used by the OBR. One difference is that it focuses on non-pensioner households. In its report it says:

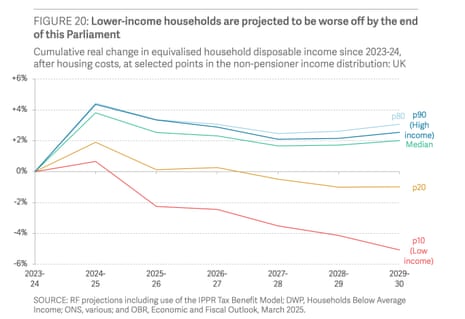

Real income of the person one tenth of the way up the income distribution (‘p10’) or one fifth of the way up (‘p20’) is projected to be lower in 2029-30 than in 2023-24, by 5% and 1% respectively. In contrast, although even higher-income households may have lower incomes on this measure by 2029-30 than in 2024-25, they would nonetheless be better off than in 2023-24 given the strong growth in 2024-25.

Here is the chart illustrating this.

And here is the passage from the report explaining the headline £500 figure.

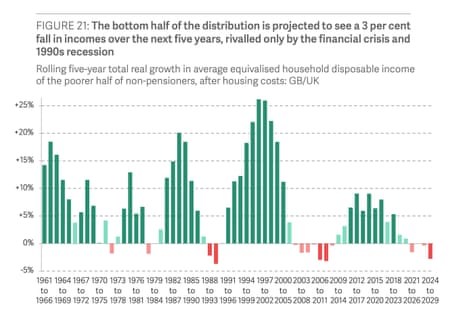

As ever, the outlook depends on many factors and is by no means set in stone, but any significant decline in incomes for the poorest in society would be historically notable. Figure 21 shows how real household incomes have grown for the poorest half of the non-pensioner population over every (rolling) five-year period since the 1960s. Over the next five years, the average equivalised income of the bottom half is projected to decline by 3%, or £500. And this scale of fall has only been (narrowly) worse during the early 1990s recession (1989 to 1994-95) and the financial crisis (2007-08 to 2012-13).

Here is figure 21.

Reeves yesterday told MPs almost the opposite. She said: “The OBR says today that households will be on average more than £500 a year better off under this Labour government.”

Why are the figures so different? Because the OBR and the Resolution Foundation are measuring disposable income in different ways. This is what the Resolution Foundation says about why its measure implies a more negative outcome.

In small part this is due to our focus on non-pensioners; but also because ‘non-labour income’ is growing disproportionately within the OBR’s RHDI projections (as the labour share is assumed to fall back), and this income may be either entirely excluded from our analysis (in the case of ‘imputed rents’); under-represented (e.g. rental income); or because it is important for average income but less so for low-to-middle income households (e.g. for many elements of investment income).

The OBR in part accepts this. This is what it says, for example, about the “imputed rent” part of its calculation.

Planning reforms boost incomes, offsetting some of the hit, as higher productivity raises wages and a larger housing stock means more compensation for housing services. Yet three quarters of the extra income from housing services comes as ‘imputed rent’ – what homeowners would receive if they rented out their home. This makes the boost less tangible for households.

Key events

There will be two urgent questions in the Commons after 10.30pm. First, a work and pensions minister will respond to a question from the Lib Dem spokesperson Steve Darling about the impact of the Pip cuts on people getting the carer’s allowance. And then a business minister will respond to question from the Tory MP Martin Vickers about the future of Scunthorpe steelworks.

Poorer households to lose around £500 per year by end of decade, thinktank says – and why Reeves is saying the opposite

In her Today programme interview Rachel Reeves was asked about the Resolution Foundation’s spring statement analysis published this morning. (See 8.33am.)

This is what it says in its summary about how the government’s measures will cost poorer families around £500.

This is still early days for this government, but it could fairly be judged not just by this spring statement alone, but in the round – considering all the choices it has taken so far affecting family finances, including at the 2024 autumn budget. Taking everything together, the burden of adjustment looks less slanted – but poorer, disabled households are still set to take the biggest hit. More generally, a combined squeeze that reduces incomes by around 1.5% in the lower-middle reaches of the spectrum declines to only 0.5% at the very top.

Factoring those distributional decisions into the general outlook for growth and income makes for particularly grim reading. Across the poorer half of the country, the five years up to 2029 will see after-housing-costs incomes drop by around £500. In data going back to the early 1960s, larger drops for low-to-middle income families have only been seen twice before – in the sharp recession of the early 1990s, and then again in the immediate wake of the credit crunch. Disproportionate income reductions for sick and disabled people in poorer households are not going to help with any of these trends.

The Resolution Foundation uses its own disposable household income figures that are different from the real household disposable incomes (RHDI) used by the OBR. One difference is that it focuses on non-pensioner households. In its report it says:

Real income of the person one tenth of the way up the income distribution (‘p10’) or one fifth of the way up (‘p20’) is projected to be lower in 2029-30 than in 2023-24, by 5% and 1% respectively. In contrast, although even higher-income households may have lower incomes on this measure by 2029-30 than in 2024-25, they would nonetheless be better off than in 2023-24 given the strong growth in 2024-25.

Here is the chart illustrating this.

And here is the passage from the report explaining the headline £500 figure.

As ever, the outlook depends on many factors and is by no means set in stone, but any significant decline in incomes for the poorest in society would be historically notable. Figure 21 shows how real household incomes have grown for the poorest half of the non-pensioner population over every (rolling) five-year period since the 1960s. Over the next five years, the average equivalised income of the bottom half is projected to decline by 3%, or £500. And this scale of fall has only been (narrowly) worse during the early 1990s recession (1989 to 1994-95) and the financial crisis (2007-08 to 2012-13).

Here is figure 21.

Reeves yesterday told MPs almost the opposite. She said: “The OBR says today that households will be on average more than £500 a year better off under this Labour government.”

Why are the figures so different? Because the OBR and the Resolution Foundation are measuring disposable income in different ways. This is what the Resolution Foundation says about why its measure implies a more negative outcome.

In small part this is due to our focus on non-pensioners; but also because ‘non-labour income’ is growing disproportionately within the OBR’s RHDI projections (as the labour share is assumed to fall back), and this income may be either entirely excluded from our analysis (in the case of ‘imputed rents’); under-represented (e.g. rental income); or because it is important for average income but less so for low-to-middle income households (e.g. for many elements of investment income).

The OBR in part accepts this. This is what it says, for example, about the “imputed rent” part of its calculation.

Planning reforms boost incomes, offsetting some of the hit, as higher productivity raises wages and a larger housing stock means more compensation for housing services. Yet three quarters of the extra income from housing services comes as ‘imputed rent’ – what homeowners would receive if they rented out their home. This makes the boost less tangible for households.

Reeves says she won’t accept free concert tickets again

In an interview with ITV’s Good Morning Britain, Rachel Reeves, the chancellor, said she would not accept free tickets for concerts again in the future.

Asked about the controversy about her decision to accept two corporate tickets for a Sabrina Carpenter concert at the O2, she repeated the line that she used at her press conference yesterday – that a family member wanted to attend the concert (presumably one of her children, but she did not say that), and that she accepted tickets for a corporate box because security concerns meant it was not deemed safe for her to get normal tickets for the auditorium.

Asked why she did not pay for the tickets, which have been described as being worth £600, Reeves said that tickets like this were not available for sale.

She went on: “I don’t have any intention of doing this again.”

Asked if she was admitting she made a mistake, she replied:

I’m just saying I wouldn’t do it again. I felt I was doing the right thing. But I do understand perceptions.

Reeves says she’s ‘absolutely certain’ welfare changes will not push more people into poverty

Rachel Reeves was on Sky News earlier. Asked about the DWP analysis saying the benefit cuts will push another 250,000 people into poverty, Reeves said this would not happen, because that analysis did not take account of the impact of more people getting into work. She made this argument at her press conference yesterday, but was even stronger in her words this morning.

She said:

I am absolutely certain that our reforms, instead of pushing people into poverty, are going to get people into work.

And we know that if you move from welfare into work, you are much less likely to be in poverty.

That is our ambition, making people better off, not making people worse off, and also the welfare state will always be there for people who genuinely need it.

Robinson ended with a broad-brush question.

You came into the job promising change – one word on the Labour manifesto. Was it our mistake not to understand that change under Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves, meant cuts for benefits for the poorest, cuts to pensioners’ winter fuel allowance, cuts to overseas aid, a squeeze on public spending, a huge new tax rise on jobs, large scale redundancies amongst public officials, and big increases in the council tax. Is that what change meant.

And Reeves replied with a broad-brush answer defending her record.

NHS waiting lists down for five months, rolling out free breakfast clubs in primary schools, the national living wage going up by £1,400 pounds from next week, 2.5% of GDP spent on defence, including £2.2bn pounds invested next year, record housebuilding, the highest level of housebuilding for 40 years. That’s the change that we promised, that’s the change that we are delivering.

Q: What are you going to do about the US car tariffs?

Reeves says there are negotiations with the US under way.

Q: You have a tiny amount of headroom. So you might be back for more tax rises or spending cuts.

Reeves says there are always risks.

But she says her policies will promote growth.

She repeats the point she made in her statement yesterday about the OBR saying families will be £500 a year better off by the end of this parliament.

Q: The Resolution Foundation says lower income families will be £500 a year worse off.

Reeves says the OBR had plenty of time to consider the plans properly, implying its verdict is more reliable.

Reeves says Darren Jones was ‘clumsy’ in pocket money comment about benefit cuts

Q: Was Darren Jones right to say disability benefits were like pocket money?

Reeves says Jones was “clumsy in his analogy” and he was right to apologise.

Q: Why does a Labour government think 370,000 disabled people should lose £4,500 per year?

Reeves says she wants to ensure sick and disabled peopel can work if they want. There are thousands of people who have been written off. The last Labour government, through the New Deal, got people into work. She wants people to be better off, she says.

Robinson plays a clip from someone with a brain injury who will be £900 a month worth on, and who says he might be made homeless as a result.

Q: What would you say to him?

Reeves says the man will stay on his benefits until he is reassessed. And then he will see a trained assessors. The people with the most severe injuries will keep their benefits, and may be paid more.

But she says the government is also putting in targeted support to get people into work.

Q: But you are cutting benefits for the disabled overall. Hundreds of thousands of peopel will lose out. The OBR says this is the biggest cut to carer’s allowance for decades. Why are people losing that?

Reeves says in the budget last year she increased carer’s allowance.

She says all the evidence shows that, with support, more people can get into work.

And even with these measures the welfare bill will continue to rise, she says.

Q: You did not mention Trump by name, but he is the reason the world has changed. But do you accept you had an impact too – your budget decisions were bad for business confidence?

Reeves says the OBR said three-quarters of the reduction in the headroom was due to global borrowing costs rising.

Q: Are you saying the £25bn tax rises in the budget had no impact?

Reeves says tax changes have consequences.

But if she had not filled the black hole in the public finances, they would not have been on a firm footing. The Bank of England would not have cut interest rates. And the UK would not have attracted as much investment.

And the NHS would not be cutting waitings lists as it is now.

Reeves interviewed on Today programme

Nick Robinson is interviewing Rachel Reeves on the Today programme now.

Q: You promised just one budget a year, but yesterday you had to announce drastic cuts. What’s gone wrong?

Reeves says she does not think anyone would claim the welfare system is working well. Those plans are about reforming the system.

But the world has also changed since the autumn, she says. That eroded her fiscal headroom. She says she will never take risks with the public finances.

Reeves says UK not planning retaliatory tariffs against US ‘at the moment’

Rachel Reeves, the chancellor, has said the UK is not planning “at the moment” to introduce retaliatory tariffs on the US, after Donald Trump imposed a new trade tax on car imports.

Speaking on Sky News, she said:

We’re not at the moment at a position where we want to do anything to escalate these trade wars.

Trade wars are no good for anyone. It will end up with higher prices for consumers, pushing up inflation after we’ve worked so hard to get a grip of inflation, and at the same time will make it harder for British companies to export.

We are looking to secure a better trading relationship with the United States. I recognise that the week ahead is important. There are further talks going on today, so let’s see where we get to in the next few days.

Graeme Wearden is covering all the reaction to Trump’s car tariffs announcement on his business live blog.

Reeves says she does not accept tax rises in autumn inevitable as she defends spring statement

Good morning. Day two after a budget-type event is when the most insightful analysis tends to come out, and this morning the two heavyweight public spending thinktanks, the Resolution Foundation and the Institute for Fiscal Studies, are delivering their considered verdicts. And Rachel Reeves is doing interviews now defending her decisions.

Here is our overnight splash about the spring statement.

Many commentators have said further tax rises are likely in the autumn. But Reeves is refusing to accept this.

In an interview with Times Radio, Kate McCann put it to Reeves:

You’re going to have to come back for more. You’re going to have to come back for more cuts or tax rises in the autumn. That’s the truth, isn’t it?

And Reeves replied: “No, it’s not.”

Asked if she was ruling out tax rises, Reeves would not go that far, but she explained why she thought they would not be necessary.

What I’m saying is that there are loads of things that this government are doing that are contributing to growth. And the Office of Budget Responsibility said yesterday that the planning reforms, the national policy planning framework, which enables us to build, for example, on grey belt land, enables building to happen more quickly, will add £6.8bn to the size of our economy by the end of this parliament. And we’ll add £3.4bn to our public finances.

That shows if we go further and faster on delivering economic growth with our planning reforms, with our pensions reforms, with our regulatory reforms, we can both grow the economy and have more money for our public services. And that is what I’m focused on.

Reeves is about to be interviewed on the Today programme.

Here is the agenda for the day.

Morning: Keir Starmer arrives in Paris for talks with other leaders about Ukraine.

9am: Richard Hughes, chair of the Office for Budget Responsibility, speaks at a Resolution Foundation event about the spring statement.

9.30am: The Department for Work and Pensions releases annual poverty figures.

10.30am: Paul Johnson, director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, and his colleagues speak at an IFS briefing on the spring statement.

11am: Jonathan Reynolds, business secretary, speaks at a Chatham House conference on trade.

11.30am: Downing Street holds a lobby briefing.

Around 12.30pm (UK time): Starmer holds a press conference in Paris.

If you want to contact me, please post a message below the line (comment will be open from 10am to 3pm today) or message me on social media. I can’t read all the messages BTL, but if you put “Andrew” in a message aimed at me, I am more likely to see it because I search for posts containing that word.

If you want to flag something up urgently, it is best to use social media. You can reach me on Bluesky at @andrewsparrowgdn. The Guardian has given up posting from its official accounts on X but individual Guardian journalists are there, I still have my account, and if you message me there at @AndrewSparrow, I will see it and respond if necessary.

I find it very helpful when readers point out mistakes, even minor typos. No error is too small to correct. And I find your questions very interesting too. I can’t promise to reply to them all, but I will try to reply to as many as I can, either BTL or sometimes in the blog.